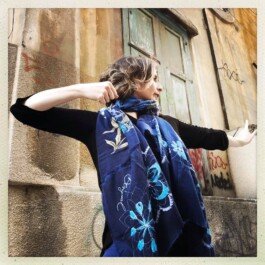

A chat with Zena Takieddine, April 2021

by Jana Al-Obeidyine

Photo credit: Heba Hage Felder

Hailing from Syria, born in the US, raised in Saudi Arabia and based in Beirut, though spending a lot of time in Dubai these days too, Zena Takieddine has been an editor and contributing writer with a Dance Mag since 2018. Today, we learn how she manages to find balance while constantly on the move.

Zena, I admire your nomadic lifestyle! How does it feel to be on the move, especially during the global pandemic?

Gosh, I’m not sure how to take your question (cringes). With so many people all over the world feeling trapped, I am well aware of how lucky I am to be able to move at all.

My gratitude to be able to do that goes fully to my father on this front. It is a long story, but if it weren’t for his ambition and foresight, this capacity for travel would not have been available, neither to me nor to anyone in my family. Like many young doctors from Syria and Lebanon during the 1970s, and especially with the Lebanese Civil War underway, my dad hoped to travel across the Atlantic and pursue his medical career in the United States. On a scholarship, he took his newly-wed wife and flew off to Cleveland, Ohio, a popular destination for medical students and aspiring physicians, famous for its Case Western Reserve Hospital and Cleveland Clinic.

As a city, though, it was a miserable one, colloquially referred to as ‘The Mistake on the Lake.’ My mother hated it there and felt very alienated; she had never lived outside Damascus before, let alone so far away from her family. I imagine those first years of marriage were quite lonely for her as.my father, career-focused, dove right into work, medical research, and moonlighting as an ER medic. That said, I owe my life to having been born in the United States, as I arrived 12 weeks too soon and spent 2 months in the neonatal intensive care unit. It’s a bit odd being raised as ‘the miracle baby’, to be honest. I’m lucky to have been so loved and supported all along the way, but I do know also that my passion for body-work and movement is driven by an intrinsic need to inhabit my body more fully, since the process of embodiment was somehow interrupted. An uncle from back home in Damascus, a famous gynecologist in his day, always told me that I would’ve been swiftly ‘flushed down the toilet’ had I been born in Syria that premature. This was an expression of his admiration for medical practice in the United States back then, especially in the field of neo-natal care. My father too having completed his medical board as a pediatrician, specialized as a neonatologist. I wonder what it must have been like for him, facing the unknown, with his young wife, my mother just 19 when she had me, realizing that sometimes things don’t go as smoothly as planned. He loves a good ‘success against all odds’ story, though, and, in some way, I feel it because his cause-célèbre to see me through those early moments of being in the world and keeping me alive. He completed his medical board as a pediatrician and specialized as a neonatologist.

Five years into American life, our little family was growing. When my twin brother and sister came along, my parents moved from their small apartment on Pepper Pike lane and bought their first house together, a proper home with a grassy lawn and a basement full of toys. Then one day, one of my father’s former professors from Beirut got in touch with him to offer him a job in an upcoming hospital being set up in the desert kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It seemed like a new adventure, and with mom eager to be closer to home, we packed up and moved back to the Arab region, this time arriving as Americans. My father made quite a name for himself in Saudi too, where premature babies were not uncommon and he excelled in his field.

So, We grew up in Riyadh, spent summers in Damascus to visit cousins and grandparents, while my parents often hopped over to Cairo for its fun nightlife and took holidays around the world.

We’ve traveled often as a family, without ever worrying about visas. We were privileged. Most people with no other documents or passports than Syrian, Lebanese, Palestinian, or what have you, get majorly harassed or restricted when it comes to travel. It is pretty uncivil if you ask me, and it has only gotten worse in current times.

The pandemic has only served to set forth stricter measures of immobility. Saudi citizens have not been allowed to leave their country since March last year, that’s one full year already. In Dubai, where my sister lives, airports have welcoming visitors and shops are all open for business while following social distancing and face-mask requirements. In Beirut, the situation is far worse, with corona deaths sky-rocketing and a defunct government betraying its people, and a financial crisis robbing the population of its hard-earned savings. Everyone has gotten more and more isolated. Syria is even worse, I can’t begin to describe.

Each reality is different. But, wherever ever are, we carry our heartbreaks and our hopes with us. We adapt, we find bubbles of safety, or spiral into depression, or simply go raging mad. Being able to stay creative is part of the safety bubble, and an outlet for depression and a channel for rage to be something useful. The nomadic life can offer a sense of reprieve, even freedom, but in the end, there’s no escaping that life is painful and that, for of all that’s being lost, it is a deliberate kind of work to reclaim some form of sanity and balance.

Since you bring up the pandemic, how has it affected you and do you find your way in these uncertain and peculiar times?

I don’t think I mind the lock-downs too much since I am more of an introvert and the halt of social obligations is actually a relief. I also appreciate that lockdowns have forced us all to simplify and connect with what really matters in living well, even if it is on a much smaller scale. I think it has been an opportunity for wisdom. Again, it is definitely easier for someone like me who doesn’t have kids and is not worried about other mouths to feed.

What’s been making most happy these days are my QiGong and Tai Chi practices. I’ve gradually made a shift from Yoga to QiGong during this lockdown period, studying and practicing. I’ve been teaching yoga classes since 2009, but I’ve found myself turning appreciating the quality of flow and presence in QiGong and Tai Chi. The anchoring spine, expanding energy and grounding stability is immediately palpable, just with the subtlest of adjustments. I am also liking them because they are practices that work well outdoors, in open spaces. It is like communion with the natural elements; trees, rocks, flowing rivers, blossoming flowers. Talk about plugging into the universe. I have deep faith in their health benefits and I love to share them, so that makes me happy. I think it is probably one of the best things to do in the middle of all this loss and chaos we are living.

Besides your yoga teaching and QiGong, I know that you are also a Somatic Experiencing practitioner. Could you tell me more about it? What drew you to it? How did you start learning? Etc.

Somatic Experiencing is a fascinating trauma healing approach that is based on perceiving one’s own autonomic nervous system and giving it the time, space and support it needs to settle and regulate itself. It is really touching the wisdom of the body. It wants to heal. We just need to allow it and not rush it.

You see, everyone’s wired differently and everyone develops certain patterns of movement and thought and behavior that, to a large part, revolve around unconscious defensive responses and needs. These are not conscious, they are in the body, in the muscles and the nerves and the viscera. We respect the human body as living breathing inter-related intelligence. Not that we get totally sucked into body processes, but we invite our mind to be present in our body and we include it and honor its wisdom for the sake of living life more fully.

If we consider PTSDs to be a kind of intense stuckness somewhere, like traces of uncompleted defensive response still buzzing in our nerves and our body, Somatic Experiences allows these impulses to be perceived and to have the space to move, very gently and carefully, like untangling a jumbled up knot in a necklace all a ball of yarn. You can’t start pulling at the whole knot, you just loosen it up and follow one thread, and that gradually untangles the rest.

It’s been a real privilege to have gotten involved in assisting SE trainings online in Arabic-speaking countries during the pandemic lockdown. We started a live workshop in Beirut before the lockdown, but when everything closed down, we discovered that it is possible to engage with people online in ways we would never have thought of before.

We, Beirut-based team members, have had an unsettling year. It was disturbing to the point that we once said that the pandemic became the least of our concerns. Do you think the Touch issue captures in some way the tragic 2020?

Actually, what struck me most about the Touch issue is that it spans the pre-Covid and post-Covid reality pretty smoothly, even while addressing complicated personal, social, political and cultural experiences from all over the world. The pandemic is woven into a much larger and richer reality. And that, I have to say, is really refreshing. I love how tangible pandemic is, but simply as a thread in the tapestry and not at all the focal point or the disrupter beyond which everything stops. There are far more intriguing stories to be discovered.

If you are to pick a story from issue 03 that had a particular effect on you, which one would you choose and why?

Haha, just one?! They’re all absolutely fascinating. I guess if I had to pick just one, it would have to be Danica van de Velve’s essay on South Korean filmmaker Lee Chang-dong’s Oasis (2002). The rendition is so sweet! I love the image of the young wheelchair-bound woman using reflections from her hand-held mirror to dance light on the ceiling and then to flirt with her care-taker… Little sparkles of light moving freely and unabashedly, how beautiful is that? It changes the whole world, just to think of it.

If you are to change one thing about a Dance Mag, what would that be?

Nothing to change, looking forward for more!